Learning Towards Liberation and Social Justice: A Model for Co-Curricular Social Justice Education

The past three years have illuminated the critical need for social justice education. That same period has also made plain the inadequacy of our existing models to meet the moment in ways that center liberation and justice for the most marginalized. The extrajudicial murder of George Floyd in May 2020 and the subsequent protests for justice launched by millions around the globe have served as an important moment of reflection about the harms perpetuated on the bodies of non-White people within the context of historical and contemporary patterns of white supremacist oppression. Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color impacted by such oppression since the founding of the United States were already aware of this reality. Further, the global COVID-19 pandemic revealed and exacerbated the stark inequities in access to healthcare as well as economic and environmental resources within the United States.

Communities impacted by decades of urban and rural divestment were already aware of this reality. In the face of these myriad challenges, many institutions of higher education offered statements and rhetorical commitments to advancing critical conversations and action toward justice. The Learning Towards Liberation and Social Justice model discussed in this piece was designed and discussed during this watershed moment—with the explicit goal of offering educators a means to actualize those commitments towards liberation for those already impacted by marginalization within the context of a co-curricular learning framework.

Developing a New Model

West Chester University launched a co-curricular learning process, designated as the Ram Plan, originating within the Division of Student Affairs. Its purpose is to provide “educational opportunities outside of the classroom that are intentionally designed to build students’ skills and competencies that complete the educational mission of the university in fostering student success.” Specifically, the division sought to design curricula formed around the following focus areas: career readiness, community engagement, health and wellness, involvement and leadership, and social justice. The social justice committee, launched in late 2020, was charged with the task of identifying theories and frameworks for the curriculum, designating relevant learning outcomes, and finally, identifying points of connection and disconnection between the existing programs and the proposed new model.

The committee consisted of four individuals, who represented three identity-based centers (which include a center for trans and queer advocacy, center for women and gender equity, and a multicultural center) alongside the campus student union.

Developing the Learning Towards Liberation and Social Justice Model engaged all members of the team in a highly collaborative, reflective, and dialogue-driven design process. First, the team gathered and reviewed existing reports and documents that reflect the participation and learning by students in various co-curricular activities. Then common understandings of key social justice terms including equity, inclusion, diversity, social justice, liberation, and intersectionality were identified and clarified. Moreso, the team discussed the limitations and possibilities of these words in the work. Most notably, social justice was defined as “educational experiences that engage students in addressing systems of oppression by developing a liberatory consciousness, engaging in processes that support healing and restoration, or participating in collective action.”

Next, the team individually reflected and imagined what social justice education should encompass to support and challenge students to learn. After discussing and sharing common points of connection between reflections, these points were used to form criteria in which to evaluate three existing models reflecting social justice education: the Social Change Model of Leadership Development developed by the Higher Education Research Institute, the Social Action Leadership Model developed by Samuel Museus at the National Institute for Transformation and Equity, and the Liberatory Consciousness Model developed by Barbara J. Love.

The criteria used included the following:

- A process or guiding questions that recognize the fluidity in this work.

- An examination of identities that understand intersectionality and are connected to systems of oppression and privilege and are given meaning over time and location.

- An examination of the relationship between power, privilege, marginalization,

and oppression. - An emphasis on self-reflection that is inclusive of the following layers: individual, community and group, and physical space.

- A definition of leadership with an emphasis on social consciousness.

- An acknowledgment of materiality as defined by concrete material examples of inequity. These inequities are also in relationship to distribution of resources including income, wealth, housing, healthcare, civil rights, respect, power, and decision-making.

- A mention of the role of “taking action.”

- An inclusion of people who hold historically marginalized identities.

- A visual representation of the model.

Each member of the team reviewed one to three of the existing models against the criteria identified to understand points of connection and gaps in the models. When components to include in the West Chester’s final model were decided upon, the team again used those same criteria to assure that it was reflective of the work. The team began the process of creating a visualization of a new model individually and then collectively. In this process, the team integrated feedback from various stakeholders doing social justice education as an important focus to their work. The stakeholders included additional staff members from the identity-based centers on campus. Their insights provided feedback that was used to create a more defined model and visualization. Additionally, the team met with other co-curricular teams that were developing their own frameworks, including the co-curricular areas of community engagement and health and wellness. There was an understanding from these teams that there can be an overlap in how social justice philosophies could also guide their areas. The Learning Towards Liberation and Social Justice Model has been shared and will continue to be shared with students to better capture their learning experiences and their understanding of the model.

Proposed Framework: The Learning Towards Liberation and Social Justice Model

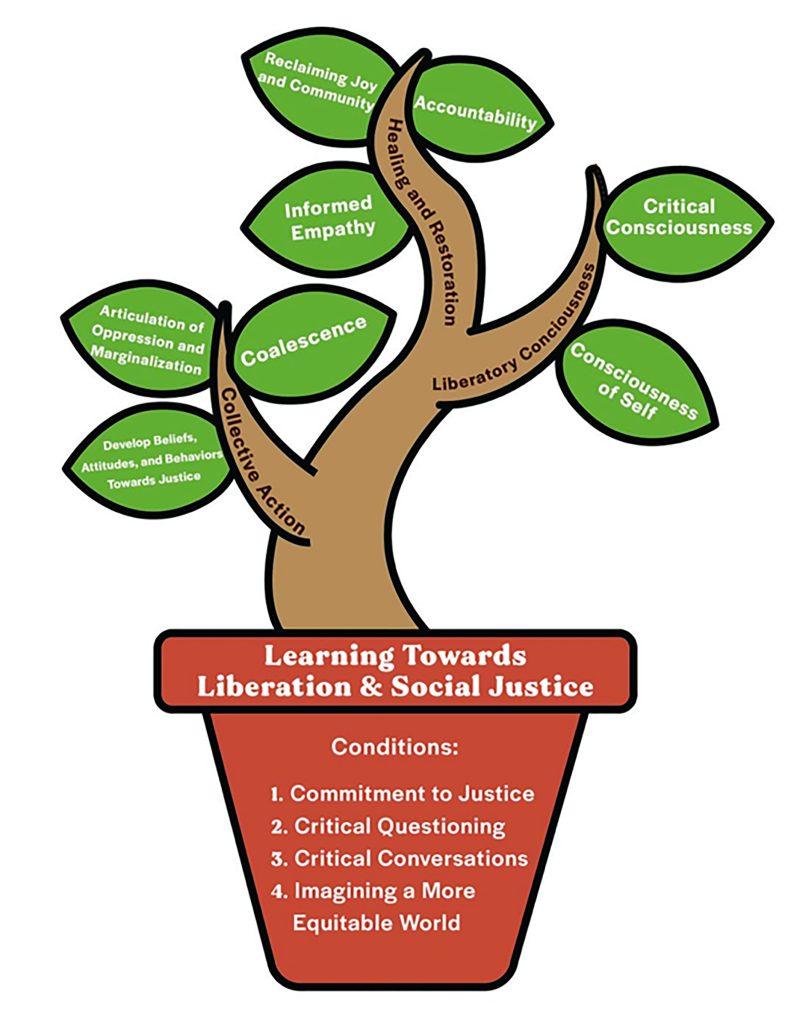

The proposed framework is displayed in a visualization of a plant and pot (see Figure 1). The image of the plant and pot provides a powerful image and metaphor for the framework that allows for movement beyond the linear model approach and creates a lifecycle of learning. The pot is the foundation and represents the conditions that must be present for learning to occur. The three branches of growth encompass the grouping of experiences for learning toward liberation and social justice. Lastly, the leaves are the areas of specific growth that are within each grouping of the experiences. All these components provide the educator guidance in supporting and challenging students’ learning. The following provides details regarding the model.

The image of the plant and pot provides a powerful image and metaphor for the framework that allows for movement beyond the linear model approach and creates a lifecycle of learning.

The Pot as the Foundation

The pot or foundation of the model represents the soil that stabilizes the rest of the plant and contains four conditions that must be met for social justice learning to occur. While it isn’t necessary for learners to meet all four conditions in one co-curricular program, the conditions still need to fully exist together to support the learners’ entire educational journey. The four conditions are:

- Commitment to Justice: A commitment to justice implies a motivation to advance the well-being of historically oppressed communities. It also entails the prioritization of efforts to achieve a more just society, where all groups are equally valued, validated, and empowered. Such a commitment requires the cultivation of agency, or a sense of empowerment, which is critical in developing the capacity to resist oppression.

- Critical Questioning: Creating questions that promote self-reflection on identities, ideologies, power, and language.

- Critical Conversations: Creating an environment that fosters an exchange of ideas as it relates to the self and one’s relationship to larger systemic issues.

- Imagining a More Equitable World: imagining a better world is rooted in a critical understanding of oppression. This condition asks and provides an opportunity for examining an alternative material truth.

Three Branches of Growth

Each branch represents a grouping of experiences for learning toward liberation and social justice. To further support this non-linear approach, each branch grows, matures, falls, and re-grows in its own continuum and is not intended to suggest a linear or sequential movement. Therefore, an individual can make progress toward the three different areas at the same time or work on one at a time. The model provides connection points between all of the areas. Finally, each branch contains leaves that offer a deeper dive into the components that make up the branch category. There are three branches in the proposed model that each hold several unique leaves that are detailed here.

Collective Action Branch:

Values of collective action are enacted when leaders work with diverse communities to collectively resist multiple forms of oppression and advance justice for all historically underserved and marginalized communities. These values can allow leaders to contribute to shared or collective agency among other social justice leaders. This branch also includes actions taken to work toward a liberated society by dismantling systems of inequity, injustice, and oppression. Leaves of this branch include:

- Articulation of Oppression and Marginalization: Knowing and understanding that inequality

and inequity exist; being able to articulate this being true; developing an analysis of the operation of power. - Develop Beliefs, Attitudes, and Behaviors Toward Justice: Inventorying one’s thoughts, language, and actions to assess whether they are currently in alignment with one’s values as they relate to justice and liberation. If they are not in alignment, this presents an opportunity to self-reflect and adjust course.

- Coalescence: The process by which individuals and groups have a shared understanding of systemic inequity and develop coalitions to address these goals. This may look like organizing, planning actions, lobbying, fundraising, educating, and motivating members of the uninvolved public.

Healing and Restoration Branch:

This branch is focused on restorative practices to repair the harm of internalized and externalized oppression and socialization over the life course and also as one seeks to engage in this work. This branch recognizes the emotional and psychological impact of this social justice work and offers a means to support consistency, perseverance, and resiliency in the face of challenges and disappointment. Leaves of this branch include:

- Informed Empathy: An ability to seek out and synthesize information to better understand people with different identities and lived experiences than one’s own.

- Accountability: The process of holding ourselves and our community accountable for the consequences of the actions that we take or do not take.

- Reclaiming Joy and Community: The act of living in joy. This can be done internally as one finds joy in themself, their identities, and their livelihood, or it can be done externally as one finds joy in a community with the individuals they convene with.

Liberatory Consciousness Branch:

An awareness of the dynamics of privilege and oppression that characterize society while cultivating and maintaining a spirit of hope toward a better future. This also takes an acknowledgment of the role that each individual plays in upholding the values the collective stands for and breaking down the barriers to social progress. Leaves of this branch include:

- Consciousness of Self: An ability to recognize one’s own identities and positionality.

- Critical Consciousness: An understanding of historical and contemporary forms of oppression (e.g., racism, genderism, sexism, heterosexism, classism, etc.) that negatively affect marginalized communities. A critical and thorough examination of power, privilege, and oppression as they have historically and currently present themselves. This may require an examination into the materiality of lived experiences of individuals and communities. Materiality also references the distribution of resources and social goods (income, wealth, housing, healthcare, civil rights, respect, power, and decision making).

Ongoing Growth and Development

Social justice education is an ever-evolving process and therefore a non-linear approach such as the one mentioned here is a great approach to allow for ongoing growth and development of not only social justice education, but the issues and topics one learns about and engages with. The proposed model of the pot and plant was carefully constructed through research, reflection, and ongoing vetting with others in a university setting. The hope is for this model to adapt as time continues and not grow stagnant in the process.

Implications, Reflections, and Next Steps

The proposed model has several implications for practice in student affairs. First, as mentioned earlier, this model was developed with the intention of using it to inform co-curricular programming. Co-curricular programming takes place in various functional areas within student affairs, including but certainly not limited to, cultural centers, student activities, residence life, and campus recreation. Although several departments are responsible for co-curricular programming, internal assessments indicate that social justice programs and initiatives have often been historically concentrated in cultural centers and other identity spaces on campus. However, for social justice to be truly effective at creating significant and lasting social change, it cannot only fall on the shoulders of those oppressed by the system to change the system. Therefore, the model is intended to be used by any and all departments across campuses to provide guidance for creating programs that center social justice.

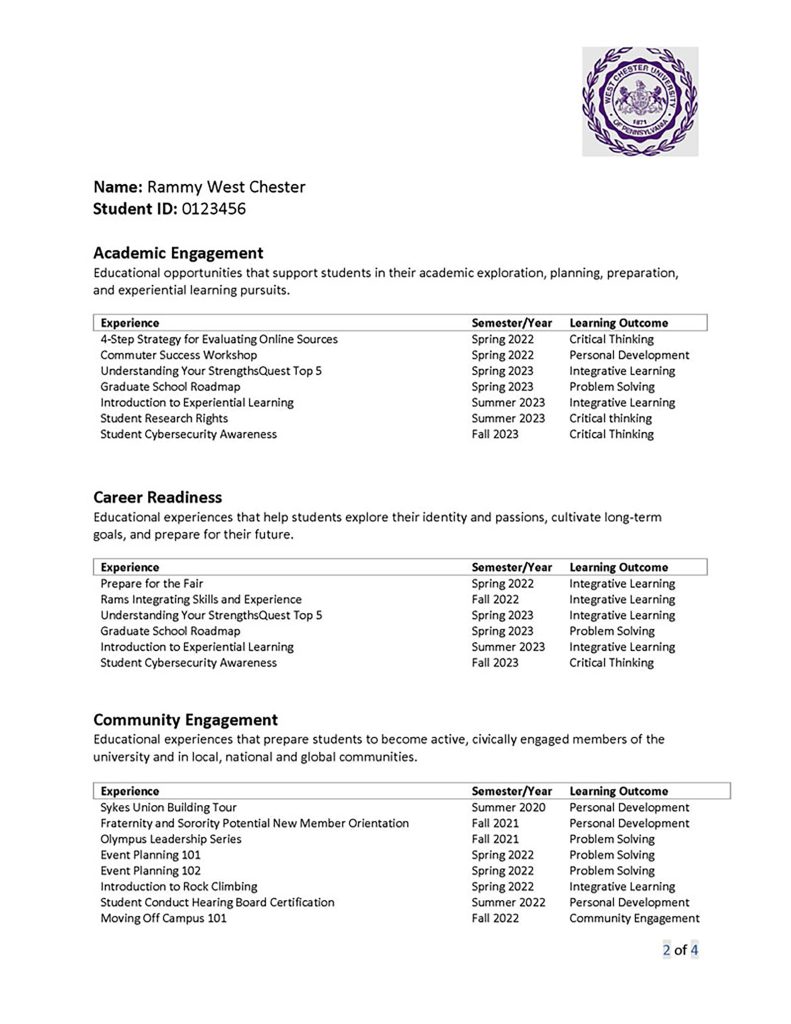

Besides allowing students the opportunity to earn valuable experience when completing educational opportunities outside the classroom through West Chester University’s co-curricular programming, students also have the opportunity to develop a co-curricular transcript that can be used in job searches, internship and graduate school applications, and for other purposes.

Using grant funding from ACUI, West Chester University piloted the model over the course of one year. During this pilot period, the team created a workshop that included a PowerPoint presentation and opportunities to engage students through this model. Some grant funds were used to purchase stickers that feature the tree model as well as T-shirts that participants would receive at the completion of attending the workshop and at least two other related campus programs. Funding was also used to provide food and snacks at workshops for the participants.

Worksheets were created to accompany the model to capture data from participant perspectives that could be used to help inform future iterations of the model. One worksheet took each of the Branches of Growth elements and asked what that area meant to the participant: For example, “What does collective action mean to you?” A word cloud of options was provided, and participants were asked to either circle words that resonated with them or include their own. Another worksheet included each branch of the model and the corresponding leaves where participants could take notes throughout the workshop to help capture the information. Both worksheets were collected at the conclusion of each workshop, scanned into a saved folder, and then returned to the student to keep for their own records. Members of the team will use this information to make informed decisions on any changes that may need to take place within the model or the presentation. During the academic year, there were three workshops completed with a total of 38 participants.

Upon reviewing the worksheets, the team noticed certain elements that participants seemed to focus on, which we found to be significant. For example, in response to the Collective Action branch, participants seemed to resonate with the words “community” and “justice.” For the Liberatory Consciousness branch, the team noted that a word like “awareness” might be more tangible for students than a word like “consciousness.” Relatedly, the team found that students might have struggled to understand the difference between “critical consciousness” and “articulation of oppression and marginalization.” The ways that they responded to the worksheet questions indicated that they may not have seen as clear of a distinction, which requires the team to now reflect on why that may be and what can be changed to make that clearer. Finally, the team also noted a further desire and need to highlight the centrality of community in this work. Participants had discussed several areas for individual learning, but it is recognized that a prominent strand of social justice education emphasizes that individuals need community for long-term engagement in justice work. Moving forward, the team plans to bring greater attention to this detail.

Conclusion

As student affairs practitioners continue to engage in social justice work on their campuses, it is imperative that they reflect on how their engagement in this work pushes their institutions closer toward liberation as opposed to relying on outdated methods that hold potential to reinforce or uphold systems of oppression. The Learning Towards Liberation and Social Justice Model serves as a contemporary framework that resists standardized forms of learning as linear and defined; it encourages a process of life-long learning that embraces fluidity, personal reflection, and community. As colleges and universities move toward implementing co-curricular approaches in and outside of student affairs, this model can assist in program creation, professional development, and strategic planning around topics related to social justice and liberation. The hope is that the Learning Towards Liberation and Social Justice Model can inspire students, faculty, staff, and community members alike to imagine a more equitable world and provide the skills needed to create it.