As COVID-19 Concerns Waned, Focus Fell on Mental Health and Campus Safety

A Jackson State University student is found shot to death in a campus parking lot; two days later, a Georgia State University student was killed across the street from the campus dining hall. At the University of New Mexico, three students were charged in connection with the shooting death of another student on campus. And on November 13, four University of Idaho students were found stabbed to death, while across the country, three University of Virginia football players were killed.

This was not an accounting of all violent deaths of college students over the past year; these occurred in just over three weeks, ending with the December 4 death of 24-year-old Joshua Igbinijesu near Georgia State’s main dining hall, less than a 10-minute walk from the student center. Also looming over 2022, was the record 300 shootings at K–12 schools (as of December 20). Managed by University of Central Florida criminal justice doctoral candidate David Riedman, the publicly available K–12 School Shooting Database put the record number at 50 more than in 2021, 186 more than in 2020, and towering over the 15 school shootings identified in 2010.

A Stanford research group last year estimated that more than 100,000 K–12 students attended a school where a shooting took place in 2018 and 2019 and researchers have long recognized that while physically unharmed, students see other consequences related to mental health and educational and economic trajectories that last for years, if not decades. The first major gun legislation passed by Congress in three decades—the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act passed in June—included $1billion for new school psychologists, counselors, and social workers.

“The unfortunate fact of me being a 21-year-old college senior is that I grew up in a time when safety at school or the movies or even the grocery store was always front of mind, and that didn’t go away when I came to college,” said Taylor Weinsz, the University of Colorado–Boulder student body president, reacting to his campus receiving a $1.2 million grant from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security that was used to begin a campaign using social media and video messaging to educate and empower the UC–Boulder campus community on violence prevention. It was also designed to improve “the systems for threat assessment and bystander reporting and response on campus, with a goal of engaging the entire campus community in a comprehensive approach to violence prevention,” the university said in announcing the grant award.

Even before the pandemic, there was recognition by university leaders of a student body imperiled by increasing mental health burdens. According to the National Institutes of Health, research from 2018 had documented a “high 12-month prevalence of psychological disorders among college students,” 31% of the population, in fact, and rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidality increased in the same population throughout the 2010s, according to a 2019 report in the Journal of Adolescent Health. Penn State’s Center for Collegiate Mental Health reported in 2015 that the number of students seeking help at campus counseling centers increased almost 40% between 2009 and 2015.

Keeping in mind that 75% of lifetime psychological disorders have onset during young adulthood, according to research in the Current Opinion in Psychiatry, universities should not have been surprised when the World Health Organization reported in 2022 a 25% increase in anxiety and depression worldwide over the first year of the pandemic.

With students fully returned to an on-campus life in 2022, and with record numbers of future students from high schools reporting depression, hopelessness, and suicidal consideration in 2021, universities had to respond in a multitude of ways.

- At Penn State, the Student Care and Advocacy Office located directly across the street from the HUB Robeson Student Center, increased its number of basic needs case managers and created a new associate director position.

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology began placing “well-being graduate resident advisors” in some of its student housing. Tasked with identifying ways to positively influence residential life and promote well-being, the program aligned with the university’s four pillars of well-being—mind, body, relationships, purpose—developed by a campus task force and the office of student well-being.

- Many campuses implemented virtual counseling and psychological services through telehealth services like TimelyCare. With telehealth services expanding over the course of the pandemic, these systems can now be crafted to allow campuses to develop their own branded apps and referral systems to on-campus services. Ohio State University was just one school that offered its own wellness app through the Apple Store, in addition to its standard mobile app.

- Emory University was one of the system’s adopting TimelyCare, but they also relied on some tried and true de-stressing techniques like fun events and lots of free food. In one week alone, leading up to final exams, Emory offered a “De-stress and Desserts,” a pancake breakfast, study halls with free snacks and drinks, “Midnight Munchies” and “Friday Night Bites” programs, and free snacks in breakrooms.

- Recognizing the dire condition of overall student mental health, Iowa State University followed suit with other campuses when it announced

in November, after collecting three years of student health data, that it would conduct a student wellness needs assessment for the sole purpose of developing a health and well-being strategic plan. - Universities began asking faculty and staff to serve as a first line of defense. Penn State’s Red Folder campaign conducted workshops and provided materials to employees to be able to “recognize, respond, and refer” students in need. The University of North Carolina provided training to nearly 1,000 staff and faculty using the National Council for Mental Wellbeing’s Mental Health First Aid program.

- Just as staff and faculty were asked to participate in assessing student mental

health, so have peers. Peer-to-peer programs increased across the United States, many supported by national organizations like

Projects Lets, Lean on Me, and Active Minds, while others operated within their own campus community. Project Rise at the University of Virginia is a nearly 20-year-old peer counseling service originally found by a group of Black students. And Duke University’s “DukeReach” program allows anyone concerned about a student’s health or behavior to submit a report.

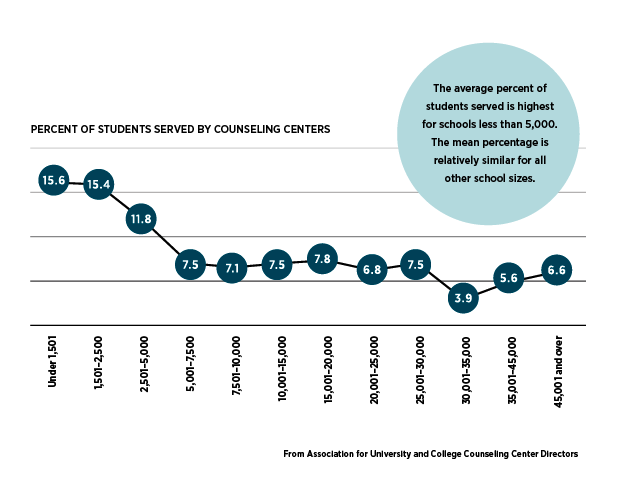

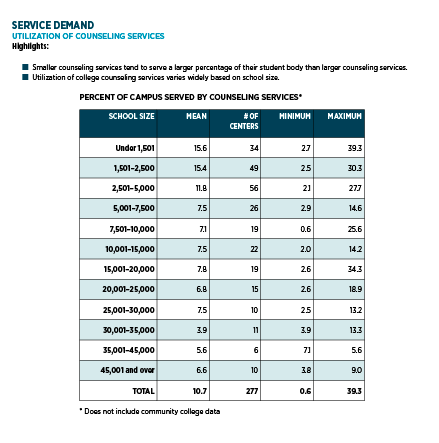

It is now apparent that campuses are going “all-in” on student mental health, and according to the Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors, it is the larger schools that have the most work to do. In its most recent annual report, for 2021, schools with full-time enrollments of 5,000 or fewer served an average of three times as many students (from 11.8–15.6%) as schools with FTEs of 30,000 and more (3.9-6.6%).

The University of Akron is a campus with a mid-range FTE between small and large schools. With an enrollment of around 15,000 students, about 8% of students receive help from a counseling center. Last year, it took the unique step of creating the new position of director of off-campus safety, recognizing a need to build partnerships, communication, and connections with everyone from landlords, area law enforcement, local elected officials, and local businesses.

This development recognizes a body of research that points to the need for a holistic, long-range approach to mental health and campus and community safety that echoes what experts have said about society in general: An individual’s physical and psychological health is often a reflection of a larger, sometimes societal-scale environment where everything from physical surroundings, technology, and how we interact with others contributes to both individual and organizational health.

Aaron De Smet, a senior partner at the McKinsey Health Institute and a co-author of last year’s Deliberate Calm: How to Learn and Lead in a Volatile World, participated in a series of interactive presentations hosted by McKinsey on prioritizing brain health. With co-author Jacqui Brassey, De Smet posits that by developing a dual awareness between self-awareness and situational awareness we can understand that “all crises are not created equal.” They describe this dual awareness as deliberate calm.

“We’re constantly faced with new levels of uncertainty, volatility. Change is now the norm. I grew up in a world where the way we think about how to handle a crisis is outdated,” De Smet said during the presentation. “Navigating conditions of great volatility and great uncertainty almost always requires a higher degree of dual awareness.”

To address crises of all types, one needs to first recognize the connection between mind and body, then practice the process of examining self-awareness alongside situational awareness, and then be prepared to put into practice a process where an individual (or an organization, eventually) asks questions like:

- What is the situation and what does it call for?

- Is this a known situation with known reactions, where the thing I would normally tend to do is the right thing?

- Is this a new and different situation where my normal habits and tendencies might not be of service?

“Which comes back to self-awareness: What are my normal habits and tendencies? What are the things I’m good at or not good at? What are my habitual reactions, and is that appropriate?” he noted.

Brassey and De Smet conducted a training program with several thousand leaders that included a control group. They found that leaders practicing deliberate calm showed three times better adaptive behaviors and outcomes, along with increased well-being seven and a half times greater than the control group.

“Our belief is that there’s a tipping point that helps a whole organization improve on these things. You’re putting in place psychological safety. The skills involved start creating a foundation of things that, when they all come together, create a bit of magic,” De Smet said.

From a smart city, to a smart campus, to a smart organization, successful frameworks that enable positive change usually depend upon, and enable, learning, social interaction, and creativity. In a place where one in five college women have experienced sexual assault, following a year where pedestrian traffic deaths reached a 40-year high, and as research consistently shows that Black and LGBTQ+ college students experience higher degrees of psychological distress and physical assault, campus leaders continue to search for ways to improve overall campus health. From limiting the use of micromobility vehicles (like e-scooters) on campuses to adapting unobtrusive surveillance systems, everything is on the table when it comes to improving student safety and mental health. The two go hand-in-hand.

That is one reason a bipartisan bill was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives last year seeking to amend the CLERY Act of 1990, which currently requires colleges to collect and report data on serious crime on campuses. It does not require them to report instances of serious harm or death related to bike or motor vehicle accidents, drowning, drug or alcohol abuse, and other accidents. The leading cause of death among college students is accidents, according to the American College Health Association; yet the 500% increase in e-scooter injuries (including fatalities) and the record number of pedestrian deaths are not reflected in CLERY reports when those incidents occurred on campuses.

As the body of research grows related to crime prevention on campuses through environmental design, the use of technology through unobtrusive surveillance systems and telehealth services, and the efficacy of programs that use peer groups, non-health professionals, and community members as interventionists, higher education will continue a problem-solving mission to address declining student health—and with the support of the federal government.

Some $76.2 billion in Higher Education Relief Funds was provided by the U.S. Department of Education to colleges during the pandemic, and they were encouraged to use those funds to bolster mental health services. Then in September, the U.S. Senate saw a bi-partisan bill introduced—the Enhancing Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Through Campus Planning Act—which has already been passed by the House of Representatives. That new legislation would require the Department of Education and the Department of Health and Human Services to institute a plan for helping universities and colleges, from small community colleges to large universities, develop and implement evidence-based comprehensive campus mental health and suicide prevention plans.

Portland State University did just that last year, when the university president approved an 83-page report—the Reimagine Campus Safety Report—that included both detailed and wide-ranging recommendations, ranging from eliminating a requirement that campus gatherings use the campus food service (to allow for more culturally appropriate foods) to reinstating an Office of the Ombudsman to allow for safe, confidential discussions by students about campus safety. Other key points included centralizing the cost of safety infrastructure within one office, rather than individual divisions; annual collection of safety metrics data and annual surveys on safety outcomes; and increasing trainings to facilitate non-violent and equitable interactions across campus.

Increased federal funding for mental health and safety services on campuses and heightened efforts to develop campuswide plans like those at Portland State are both supported by survey data collected by crisis communications and preparedness companies. One company, Rave Mobile Safety, talked to nearly 400 higher education staff members and 59% said student mental health, followed by staff mental health (44%), were top concerns in the coming year. Nearly half of those surveyed, 46%, said they were more concerned about active assailants and violent acts than they had been prior to the pandemic.