A Third Home: Communities Gravitate to a Space for Learning, Engagement, and Honest Conversation

A foundation of the Role of the College Union is that it “advances a sense of community, unifying the institution by embracing the diversity of students, faculty, staff, alumni, and guests.” That call to action earmarks the college union as one of those “third places,” the term coined by urban sociologist Ray Oldenburg denoting public places as “neutral ground where people gather and interact.”

“Life without community has produced, for many, a lifestyle consisting mainly of a home-to-work-and-back-again shuttle. Social well-being and psychological health depend upon community,” wrote Oldenburg in his 1991 book, “The Great Good Place.” “Though a radically different kind of setting for a home, the third place is remarkably similar to a good home in the psychological comfort and support that it extends … They are the heart of a community’s social vitality, the grassroots of democracy, but sadly, they constitute a diminishing aspect of the American social landscape.”

A public space serving as a “good home” mirrors the long-used analogy of the student union as the “living room” of campus, so when someone like Patrick Wallace, associate director of campus center and student involvement at Rutgers University–Camden, describes the campus center there as a “third space” he is describing the inherent value of that space as one of continuous learning, for public engagement, and as one providing a public platform. It’s where conversations on current day issues can be held, where workshops are hosted, where storytelling occurs, where anyone can be present.

The accessibility and the diversity of the college union space is why Wallace is among the group of professionals, students, and community members who recognize it as the perfect venue for participatory learning projects like Hostile Terrain 94, or HT94, which raises awareness about the realities of migration at the U.S.-Mexico border. Created by the Undocumented Migration Project, the pop-up installation has been displayed hundreds of times around the globe, in art galleries, libraries, academic buildings, and particularly in student unions across the U.S.

“The Hostile Terrain 94 installation allowed our Campus Center to serve as host to a variety of programs relating to various topics inherent to the project, providing multiple opportunities for the Campus Center to serve as a continuing learning space for our campus community beyond the walls of the academic classroom,” Wallace said. “It allowed for conversations amongst our campus community ranging from the theoretical to the practical to the ethical.”

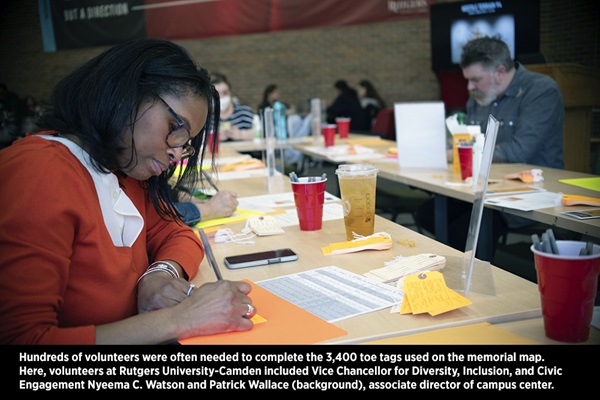

The core element of the exhibition is a memorial wall map that contains roughly 3,400 toe tags representing people who have died while crossing the U.S./Mexico border between the mid- 1990s and 2020. Manila tags represent those who have been identified, while orange tags represent unidentified human remains. The construction of this memorial is realized with the help of hundreds of volunteers—in this case students, faculty, and staff—who hand-write the information of the dead. These tags are then placed on the wall map in the exact location where those remains were found.

Having organizing communities engage in the process of writing around 3,400 toe tags provides people with a very direct and meaningful experience that effectively communicates the humanitarian aspect of the work. The physical act of writing out the names and information for the dead invites one to reflect, witness and stand in solidarity with those who have lost their lives in search for a better one.

Participants were also invited to leave a message or drawing on the backs of their toe tags, as a way to reflect and further engage with the project. Thoughtful works of art were created on many tags, as well as messages of remembrance, love, and calls to action. Examples from one exhibit, at the HUB-Robeson Center art gallery at Pennsylvania State University, included: “I will fight for you and your people to come here for a better life so that no one suffers the same fate. Rest in peace.” Other sentiments read, “You matter,” “You are valued,” and “You are not forgotten.”

Penn State organizers enriched the exhibition through class partnerships with faculty on several campuses, connecting with disciplines like anthropology, sociology, visual arts, education, and literature. Faculty utilized HT94 in courses across the U.S., including in Penn State’s Public Writing Initiative that brings students from various writing courses into contact with community organizers and professionals who use writing daily. Sarah Felter, a comparative literature student at Penn, described what filling out these tags meant to her:

“I squinted, attempting to read the final cell in my spreadsheet to write on my remaining toe tag. I had made a few mistakes already, but this was it: the final one. As I write the cause of death in the proper section, I realize I wrote it incorrectly and I have run out of tags. I put them down on my desk and take a minute. It took me much longer than I anticipated to fill them out and I was struggling to read what was on the sheet, causing me to have to slow down and take my time with each one. Part of me wonders if this was done on purpose, forcing us to consider each part of what we write down. Taking a step back, it feels wrong to be frustrated with writing ‘skeletal remains’ on the wrong line. I am upset because it is taking more time than I want it to, but ‘unidentified’ has no time left.”

Student centers that hosted Hostile Terrain 94, like the ones at Middlebury College, the University of Nebraska campuses, Mississippi State University, Boise State University, Portland State University, and Northern Illinois University were often thousands of miles away from the Sonoran Desert, but the distance one had to travel in order to empathize with and contemplate on the stories of those who died did not need to be far at all. When filling out the toe tags was augmented with virtual or on-site wayfinding experiences, relevant videos and movies, associated art exhibits, public readings, and personal testimonials, the experience often became immersive.

The wayfinding experiences were conceived to highlight the exhibition as less a map and more as a memorial to lives, with individual stories and messages told to visitors as they worked their way through a series of stations. The final destination may have been the HT94 memorial wall map, but the stations prior were designed to share messages left by those who died on their journeys and by those who knew and loved them. Associated Quick Response (QR) codes were placed on posters at each stop, providing links to webpages where participants could listen to immigrants telling their stories. The stations directed them to information about legislation influencing dangerous immigration tactics, and to videos of people mourning their loved ones or who were still searching for those who

went missing.

There is also a virtual documentary experience that pairs with the physical installation. The virtual experience contains five chapters where viewers can hear first-hand accounts from migrants and humanitarian volunteers, represented by archival photos and volumetric captures, hologram-like videos. Viewers can navigate and select chapters from an interactive map, click on 360° environments, and explore 3-D models of real-life items left behind by migrants and found in the Sonoran Desert. At the end, viewers have an opportunity to add their voices to a memorial.

The story of Marisela Carmita Zhagui Pulla was one that some students said would be etched in the minds of many. Her last words, shared with her family before she attempted to cross the border, were: “I don’t know how I’m going to get there, but I’m going for my family, God willing, I will get there.” She was later found dead in the desert by Dr. Jason De León, the creator of the project, and

his team.

Gustavo Espinosa, a business undergraduate at the University of Rutgers—Camden who is a member of campus Latin American Student Organization, said the experience was an opportunity for people to understand how big the problem of immigration was. He was surprised that people weren’t more vocal about the issue, including migrants and first-generation U.S. citizens whose parents had crossed the border.

“There should be a solution to this border crisis, no human should go through these harsh conditions staring death in the eye, in order to have a better standard of living. These are moms, dads, children, elderly, and pregnant women walking in the hot desert, bringing as little water and food as possible so as not to carry the weight that would have them exhausted early in the journey.

“I felt connected to Hostile Terrain 94 because my whole family, including grandparents, my mom, aunt, and uncle crossed the border together in the 1990s. My mom and aunt were barely teenagers and my uncle was only seven. That breaks my heart, because my brother is only seven and I can’t imagine him walking in harsh conditions with barely any water, extreme heat, snakes, barely any food, and facing exhaustion. This is not just my family, but my friends too. The majority of my friends are Mexican and have the same story of how their parents crossed the border. Every time I stepped a foot inside cc and looked at HT94 I took a moment to be grateful to my family and other families for what they have done for their future generation to have a better quality of life,” Espinosa said.

Robrecht van der Wel, an associate professor of psychology at Rutgers–Camden who led the effort to bring HT94 to campus, has followed the work of the University of California–Los Angeles Anthropologist Jason De León since they were graduate students together. He first used examples of De León’s early work, visual displays of the actual backpacks lost in the Sonoran Desert, as a unique way to teach research methods. “I noticed how much it captivated our students,” van der Wel said. “That exhibit was fairly costly, prohibiting broader dissemination. Hostile Terrain 94 is a powerful, cost-effective way to communicate … one of its biggest strengths is its participatory nature.”

Programming at Rutgers–Camden also included a presentation on the ethics and forensics of identifying human remains, a symposium on the rights of children at the border, and a visit and presentation by De León himself. While there, De León visited a charter school, engaged high school seniors in filling out toe tags, and participated in an off-campus community-wide event.

“Our main purpose as a university community is to be centers of knowledge and foster broad understanding,” said van der Wel. “Hostile Terrain 94 provided a way to bring an honest conversation about migration to our campus. I found this to be particularly important to provide a more informed and humane perspective on migration while negative and simplistic statements about the migrant problem at the Southern border were very prevalent. The campus center was an excellent space to foster a campus community and organize events on issues that touch all of our students, faculty, and staff. Students naturally gravitate to spend time there and have been very open to engage in conversation surrounding Hostile Terrain 94.”

A gallery in a college union is an added benefit to using participatory art projects as learning tools. Over the years the gallery in the HUB-Robeson Center has hosted performance art pieces, collaborative drawing projects with the surrounding community, multi-media events that included light shows, fashion shows, drag shows, and dance, and creating inflatable sculptures using recycled materials. Earlier this year the gallery hosted “Lunchbox Moments,” an exhibition of painted lunch boxes narrating the Asian-American experience as formative occurrences in many Asian Americans’ lives, where a traditional Asian meal is eaten at school or home, and the meal elicits some sort of reaction-—be it positive or negative. Workshops with the artist, Ami Bantz, gave students the opportunity to share their own ‘lunchbox moments’ and to create lunchboxes and bags that were then displayed in the HUB-Robeson Center.

Sustainability is one topic that often finds itself manifested in student union galleries. A number of them have hosted “upcycling” fashion and art shows, and the gallery at the Southern Illinois University Student Center had various campus divisions set-up interactive displays tied to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals. At Louisiana State University, the campus women’s center and the student union art gallery collaborated earlier this year to create a Sexual Assault Awareness Month exhibit called “What I Wore,” where abuse, rape, and assault survivors anonymously donated clothes or descriptions of clothes they were wearing at the time of the incidents. The exhibit garnered national attention.

When Hostile Terrain 94 came to Smith Memorial Student Union at Portland State earlier this year, the building’s White Gallery provided a space for ofrenda, or home altars, to be created using sweet breads (pan dulce), sage, and other items. The gallery’s beams were adorned with papel picado, an artform using brightly colored, elaborately cut sheets of tissue paper.

And at Middlebury College, while Hostile Terrain 94 was being created and displayed in the McCullough Student Center’s art gallery, a huge mural along the ground-floor level served as evidence that education, community building, and art, can rise anywhere in the college union. Begun in 2018, the mural was directed by a group of professional muralists and community organizers who also conducted introspection, design, and painting workshops

with students.

The mural project was a follow-up to a year of artist in residence Will Kasso Condry leading student workshops that resulted in corridors and stairwells of the campus intercultural resource center being painted with murals, including large portraits of the center’s namesakes—Mary Annette Anderson and Martin Henry Freeman—at the building’s entrance. For the McCullough Center mural, Condry joined three other artists for the weeklong residency of painting workshops and creation of the new mural inside the student center.

When Oldenburg discussed “third places,” he attributed them to having a series of important functions, including as unifying, caring, and entertaining spaces; as “sorting areas” where those with special interests find one another, and as “ports of entry” for visitors and newcomers. Finally, he noted, they are places for political debate where social networks can be strengthened, and social problems addressed.

In examining Oldenburg’s work, Felice Yuen and Amanda J. Johnson, Canadian social scientists who study public leisure spaces, note that “just because a space is public does not mean it is democratic or accessible.” They agree that place can be seen as a social construct, relying on the enjoyment, regularity, pure sociability, and apparent diversity, but add “diversity is the most relevant when exploring third places as a platform for community. … If we talk about leisure spaces as places of community, then we should be discussing who is present and who is not … The requirement for diversity narrows the spectrum of leisure setting that may be considered a third place.”

If that is the case, the college union stands on firm footing as a confirmed “third place”—not home (the first place) nor work (the second place)—where participatory experiences like Hostile Terrain 94 can successfully educate, elicit empathy, create community, and identify shared values.